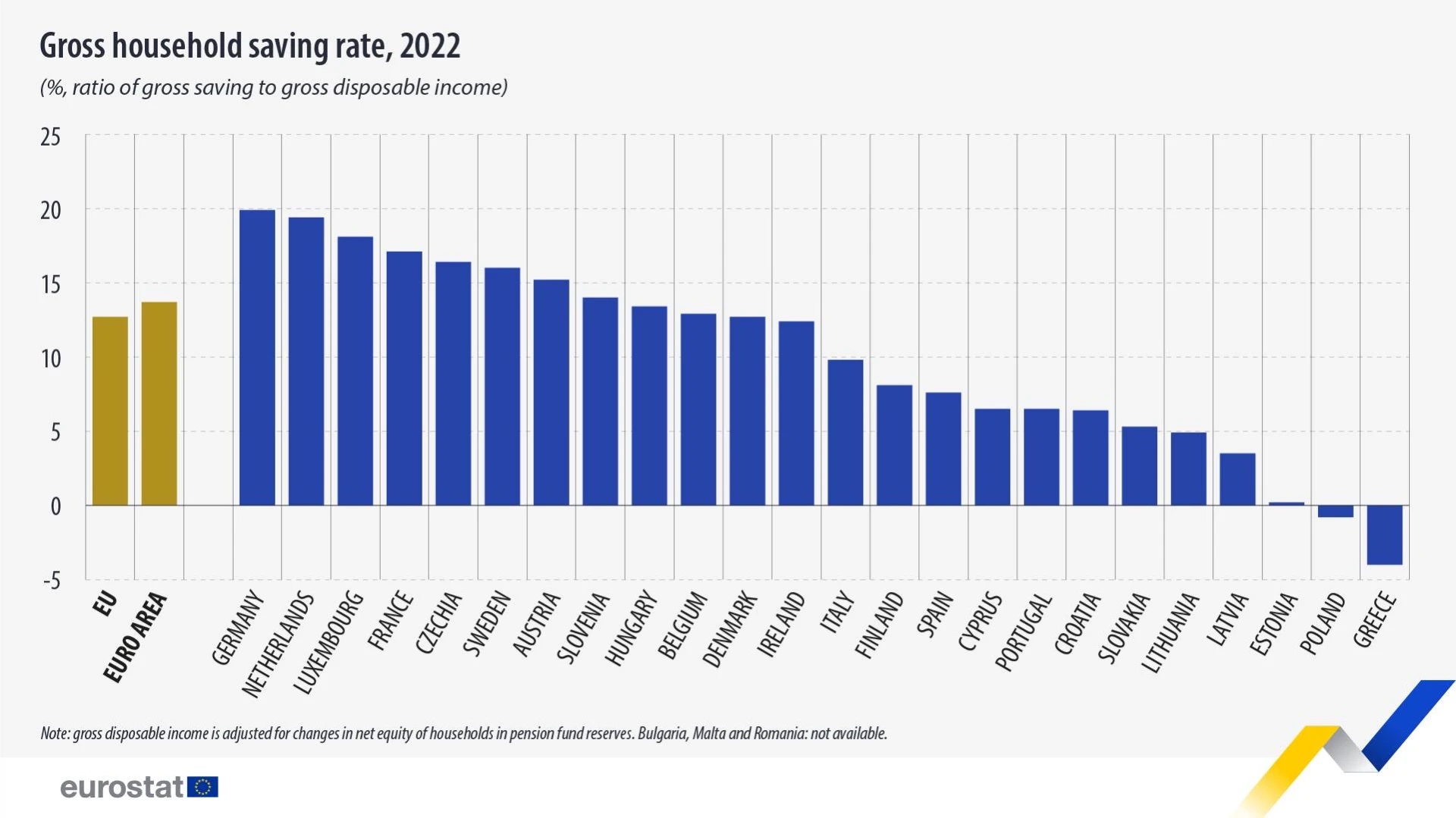

The latest data on savings present food for thought for the Greek government policymakers regarding its exit out of the woods. In 2022, people in the EU saved on average 12.7% of their disposable income. The rate was significantly lower than in 2021 (16.4%), and closer to the values before Covid-19 pandemic. The highest gross saving rates among the EU members in 2022 were recorded in Germany (19.9%), the Netherlands (19.4%) and Luxembourg (18.1%).

Twelve EU members recorded saving rates below 10.0% in 2022, among which Poland and Greece had negative rates, -0.8% and -4.0%, respectively. This indicates that households spent more than their gross household disposable income and were therefore either using accumulated savings from previous periods, or were borrowing to finance their expenditure, especially Greece.

The fundamental macroeconomic accounting identity is that (in a stable equilibrium environment) the sum of private savings and government taxation equals that of private investment and government spending (S+T=I+G). To a large extent, private investment is supported by private savings and taxation finances public expenditure, so the private sector operates in a collaborative environment with the public sector. You cannot pursue prudent fiscal policy without following these elementary economic rules and principles. But when the public sector intervenes in this relationship at the expense of the private sector, then it undermines its own sustainability, and this because according to the economic reality it contributes to potential effects of displacement of private investments (crowding out effect). The message from the EU data is that the Greek government’s high levels of taxation, coupled with its incompetence, have contributed to this very dangerous situation.

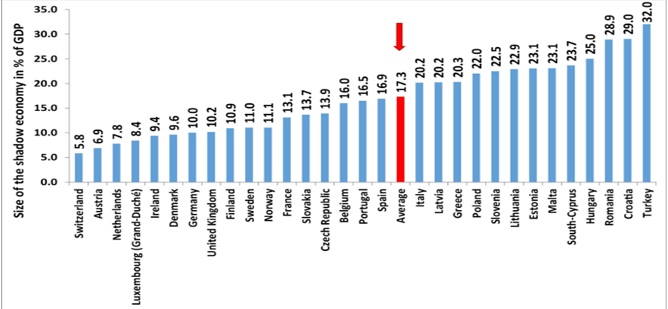

A confirmation of this also lies in complementary data which shows Greece’s shadow economy to be 20.3% – i.e. even higher than the EU average of 17.3%.

This is also confirmed by the Greek central banker, who recently stated that “Greeks consume €40 billion more than they declare to the tax office,” implying that the scale of the shadow economy is around 20% of the official economy. All this points to a large bureaucratic state which is unable to modernize because the state has become autonomous and is controlled not by citizens and politicians, as it should be, but by civil servants and executives of the administration which possess the information, know the procedures, and process the laws in such a complicated way that the ordinary, everyday Greeks have been alienated and the great majority of them feel and behave as individuals and not as citizens.

Yet, a government officer working in Greece will typically earn around 38,180 euros per year, and this can range from the lowest average salary of about €18,780 to the highest average salary of €57,900. These salaries are by far higher than those in the private sector, which according to the National Social Security Fund (EFKA) in 2023 for full-time workers in the private sector is €1,182.39 per month. According to Statista data in 2022, average annual salaries in the EU ranged from €24,067 in Greece to €73,642 in Iceland. Statista’s figures are for 2022, but the situation regarding wages is worsening in Greece. A greater weight for this average is attributed to government wages as we have already noted earlier.

Finally, current policy settings in Greece are not inspiring and this is a point that warrants much reflection and a genuine desire to stabilize this situation.

Source : Ekathimerini