ATHENS — Christos Rammos is turning the screws on Greece’s government.

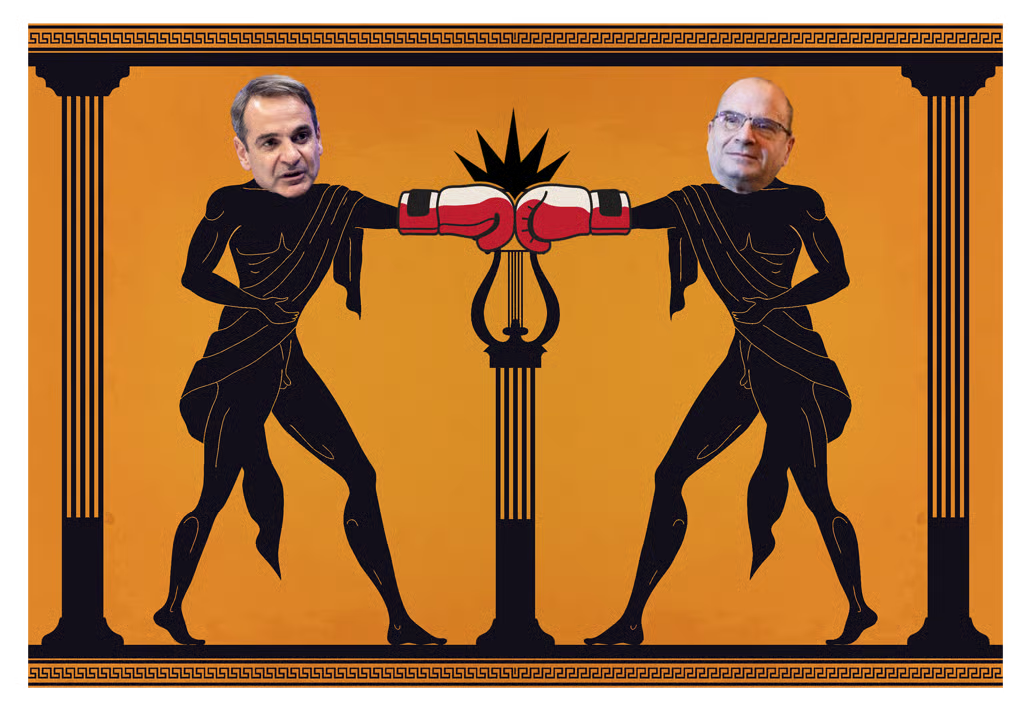

Rammos has been the key investigator of the surveillance scandal that has engulfed the Athens government and its leader, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, since the summer, and is piling pressure on the ruling conservative party New Democracy ahead of the next election, which will likely take place as soon as April 9 (or by mid-July the latest).

The 72-year-old bespectacled former judge leads the Hellenic Authority for Communication Security and Privacy (ADAE), a previously inconspicuous regulator that is now leading some of the hardest-hitting investigations in government services’ use of spyware to snoop on top politicians, senior state officials and journalists — a scandal that has spiraled into Greece’s own version of the U.S.’s 1972 Watergate intrigue.

To the government’s supporters, Rammos is a “delivery boy” of the political opposition who has reached “far beyond the limits of his role” in investigating the scandal. But for opposition and civil society groups, the chief regulator is a hero who broke Greece’s code of silence around political snooping — a glimmer of hope in keeping the government’s powers in check and restoring balance to Greek democracy, where press freedom has suffered setbacks and insiders complain of cronyism politics.

“I am presented as a tool of the opposition in the worst case, or else as a strange Don Quixote, an obsessed man who is out to become the savior of democracy,” Rammos told POLITICO in an interview in his living room in Athens, surrounded by books and his cat Zoi (“life” in Greek). “I’m just doing my duty. And that’s considered exceptional nowadays,” he said.

Rammos is due to address members of the European Parliament’s inquiry committee investigating the use of spyware in Europe (PEGA) on Tuesday.

At home, the chief regulator is up against the country’s most powerful people.

The surveillance scandal unfurled in August, when it was revealed that the government had wiretapped the phone of Socialist Pasok leader Nikos Androulakis — a move the government itself called legal but wrong. It has since led to the resignation of top government officials like Grigoris Dimitriadis, the prime minister’s chief of staff who’s also Mitsotakis’ nephew, and Panagiotis Kontoleon, who was head of the National Intelligence Service.

Revelations by investigative journalists, civil rights organizations and Rammos’ own regulator ADAE told a labyrinthine tale of how the country’s state spy service had an ever-expanding network of politicians and journalists under surveillance, while controversial spyware like Predator was planted on the phones of some people at exactly the same time by as-yet-unknown perpetrators.

The government dismisses allegations that the scandal goes up to Mitsotakis himself and says any wrongdoings were done by “foul networks” within the intelligence agency. It says that there is no proven link between the “lawful” but “wrong” wiretapping by state officials with the use of spyware; that a judicial investigation is ongoing; and that opposition party Syriza is hypocritical in raising the issue of the rule of law after a recent ruling found an ex-minister of the party guilty of breach of duty over a 2015 TV licenses bid.

Step by step, Rammos is laying bare the painful details of the government’s actions. His authority has conducted audits that revealed how state officials had been under surveillance by the spy agency. He has provided evidence to the Greek parliamentary committee investigating the scandal behind closed doors and has continued audits despite facing public pushback in pro-government media.

His findings have hit Greek politics at its core, despite attempts by a Greek supreme court prosecutor and the ruling New Democracy party’s legal and parliamentary challenges to block them from becoming public.

“From an unknown authority, ADAE unwittingly became a protagonist,” Rammos said. He said the slow pace of Greece’s judiciary is holding back a more thorough oversight of the intelligence agencies’ surveillance powers.

Accusations of ‘treason’

ADAE’s last audit took place at the request of the main opposition Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras and unveiled that six more senior state officials, including the heads of the Greek armed forces and the labor minister, have been placed under surveillance by the state spy service (EYP) for up to two years.

Rammos asked to inform the parliamentary committee confidentially of his latest findings, but New Democracy blocked it. He then sent a letter describing his findings to the party leaders and Tsipras published them in the parliament, calling the government to resign.

Attacks against him multiplied after this last audit. Government spokesman Giannis Oikonomou called Rammos’ actions “a serious blunder, institutional and political,” adding that he “obviously aspires to become a political actor in a sensitive period.”

“Rammos has touched the boundaries of treason and not just the legal order,” said Development Minister Adonis Georgiadis.

But the regulator, who was a judge for 38 years, is sticking to his line that it is simply his job to scrutinize the government’s use of spyware. “In Greece there is a tendency to suspect that everything in public life is done in a partisan way, that there is a hidden political or personal agenda behind every decision. The possibility of being a proper and honest professional is not accredited,” he said, adding, “nothing could be further away from my personality, mindset and aspirations than a political career.”

Pro-government media have called on him to resign.

But “I never thought of resigning. Not for a moment. No one can dictate that to me,” he said, adding that his term ends on May 2025. “When you have to deal with slander, lies and hatred, it might occur for a moment that you wish you would better like to get rid of all of it. But for me, duty prevails.”

Threats of legal action against his authority, however, can have a “chilling effect” on his staff, he warned. “Where there is fear there is no democracy. Democracies need a calm environment and respect [for] the personalities [conscientiously doing] their job, even if we disagree with them,” he said.

Above all, the regulator is working to restore the power of independent watchdog institutions like his own privacy authority — and, through it, also restore Greece’s democracy.

“In Greece we have not really understood what independent authorities are for,” Rammos said. “The culture of all parties over time has unfortunately mainly been that independent authorities are good and welcome as long as they do not annoy us, but whenever they become unpleasant, we attack them. We consider them intruders.

“We are dealing with an ongoing crisis in the domain of the confidentiality of communications,” he said. “It’s usual for democracy to have crises and it has the means [to] overcome them, but this needs constant vigilance and sometimes courage too.”

Source : Politico